The Monashee Almanac is an online journal that shares history, mysteries and stories about early British Columbia and in particular the Monashee, Okanagan and Shuswap.

Celebrating History, Mysteries & Stories

The Official Account of Gold being Discovered in Cherry Creek

“…he took four handfuls of sand from the creek and washed it in his frying pan.”

the Chief Commissioner of Lands and Works (CCLW), responsibility for marking out all the proposed towns and Indian reserves in the colony.

I

n March 1861, Governor Douglas gave R.C. Moody,

snow

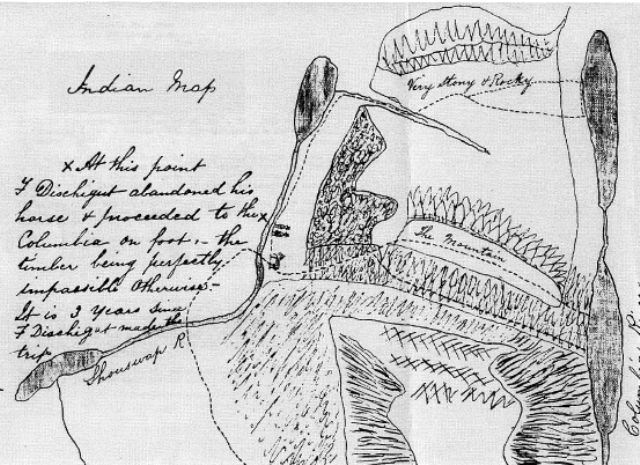

In 1862, Cox drew a sketch, in the lower left hand corner of the map, showing the mountain that was facing them. It looks like The Pinnacles, a group of peaks that tower over 8,000 feet, and although it was the middle of summer, Cox wrote the word “snow” at the top of his mountain sketch.

He also directed Moody to give instructions to the newly appointed Assistant Commissioner of Lands and Works (ACLW), W.G. (William) Cox, who was to carry out this work in the Rock Creek District.

Cox's report of the journey that included the "Map of the Proposed Road," was entered into the governments official Colonial Correspondence on August 8th 1862 which represented the first time that the travel route to the area we now know as Cherryville or the Monashee is indicated as a “place”. However, the details of the journey and the linen map had become an obscure footnote in BC history – and then largely forgotten, in fact the map was lost.

In July 1986, a previously unknown linen tracing of a map was found in the Surveyors General’s office in Victoria. The linen map had been lost for nearly a century and the discovery moved researcher Robert L. de Pfyffer to compile the intricate information found on the map and then to place it into context using other available historical information including land records and government reports.

He published his findings in the 51st Report of the Okanagan Historical Society in 1987. His work was titled, Trails: Found - Cox’s Map of 1862. The story is driven by the discovery that Governor Douglas ordered W.G. Cox to mark a Government Reserve that was ten miles square or 100 square miles in order to claim land for the beginning of a road east to the Columbia River. Cox placed the claim post in what is now Coldstream.

The Robert L. de Pfyffer Story

As the Assistant Land Commissioner, Cox kept detailed records including a land record book. Here is what Robert L.de Pfyffer wrote beginning with Cox’s entry in 1862.

Rock Creek Land Records 1860-1862

Compiled by W.G. Cox

Record Number 32, July 26th 1862

Recorded for a Government Reservation

- Ten miles square from a central point marked by a prominent stake and situated about five miles from the head of Lake Okanagan on the East side – being the terminus of the projected road between that lake and the Columbia river,

- The above Reservation is situated in a fertile sheltered valley – is well wooded and watered with abundance of excellent grass.

Why did Cox mark out this enormous reserve?

The answer to this question is found by going back to June 15th 1846 when the British and the Americans signed the Oregon Treaty which divided the Oregon Country into two parts along the 49th parallel. South of the border the Americans found it relatively easy to travel from west to east through their Oregon Territory. North of the border, in the land that the British eventually named the Colonies of Vancouver Island and British Columbia, travel from the west to the east was barred by many ranges of mountains that ran from north to south. When it came to traveling, the people of British Columbia, had a problem and the discovery of gold in several places in the Colony forced the government to improve communications be searching for new passes through the mountains.

Early in 1862 the Colonial Secretary, William Alexander George Young was instructed by Governor Douglas to send W.G. Cox a letter asking him to find out if there were any routes through the mountains between the Okanagan and the Columbia valleys. On April 7th 1862, Cox replied that his Indian friends and Mr. François Dischigut (sic) knew of at least two routes. The southern route started at L’Anse au Sable, near the Okanagan Mission and it went straight east to the Arrow Lakes. The northern route started close to the head of Okanagan Lake and it too went straight east to the Arrow Lakes. With his reply Cox submitted a sketch map of the area showing two routes. For some reason Cox was under the impression that there were three Arrow Lakes, not two. His sketch map shows three lakes and in his correspondence he often refers to the middle Arrow Lake.

Actually there was nothing new in Cox’s report, because the fur traders had long been aware of the fact that the Okanagan Indians and the Lakes Indians used a trail connecting the two valleys. Archibald MacDonald, in his 1827 sketch of the Thompson River District, shows a trail connecting the Okanagan and Columbia Valleys. True Mabel Lake and Sugar Lake are located to the far north in MacDonald’s sketch, but the sketch proves that the fur traders knew of the trail’s existence.

After Young received Cox’s report, he gave it to Governor Douglas for his perusal. Douglas wrote a long note on the report telling Young to write to Cox with instructions to explore the northern route and to submit a detailed report on his findings. Douglas said that if Cox found a suitable route for the road, he was to mark out a Government Reservation for public use at both ends of the proposed road. Cox was also instructed to look for gold because Douglas felt that an influx of miners would help to build up the prosperity of the Colony.

Cox followed Douglas’ instructions and in July 1862 he went to the northern end of Okanagan Lake where there was an Indian community that the Okanagan’s called Nkama’peleks. This name is still used by the Okanagan’s today and it simply means the “Head of the Lake”. When the early French Canadian fur traders arrived at Nkama’peleks they discovered a cluster of spruce trees near Tsin-th-le-kap-a-lax (Cayote) Creek. Now known as Irish Creek. To the fur traders the presence of spruce trees at this low elevation was very unusual and for this reason they called the place Taillis or Talle d’Epinette’s a name which translates into English as Spruce Grove. Even up to the late 1870’s the Indians from Nkama’peleks were called the Taillis or Talle d’Epinette’s in order to distinguish them from other Okanagan Indians.

In his report to Young, Cox states that he left “Talle d’Epinette’s” on July 17th for the purpose of exploring the road to the Columbia River. He had engaged two Okanagan Indians from Nkama’peleks as his guides and each guide brought one of his sons along. Cox wrote that these men were the only people in the country familiar with the route and their last trip to the Arrow Lakes was made three years earlier.

By July 26th, Cox with his guides had returned from their exploratory trip and they planted a post in Coldstream to establish a one hundred square mile Government Reservation. On August 8th Cox completed a map of the Indian trail from Okanagan Lake to the Arrow Lakes and he sent it, together with his written report, to W.A.G. Young, the Colonial Secretary. Young forwarded Cox’s map to the office of the Chief Commissioner of Lands and Works where a tracing was made on linen. It is this previously unknown linen tracing that was found in the Surveyors General’s office in July 1986.

The tracing of Cox’s map is 18”x 36” and it is not drawn to any particular scale. A trail with several branches is shown running from Okanagan Lake to the Arrow Lakes. Numerous hand written notes cover the drawing, presenting a tremendous amount of information, much of which Cox obtained from his guides. Very few place names are shown, in fact there are only three place names viz, Head of Okanagan Lake, Shouswap R. (sic) and Middle Lake, Columbia River. In order to describe the map in greater detail, it is necessary to use today’s place names.

The map indicates that highway No.6, between Vernon and Lumby practically sits on top of the old Indian trail. From Lumby to the old bridge site, below Shuswap Falls on the Shuswap River, again the road closely follows the old Indian trail. On the left hand side of the map, Cox shows the “Head of Okanagan Lake” and three trails starting at or near the Lake, all of which pass through Vernon. At Vernon Cox drew a number of hills, several of which now have names like Middleton Mountain and Black Rock. All three trails combine to form a single trail just before crossing Coldstream Creek. In an open area immediately after the trail crossed the creek, a post is shown on the map with the note, “Gov’t Reservation 10 Miles Square”.

From Vernon to Lumby, Cox noted that the trail passed through “a rich fertile valley.” At Lumby, he indicated that a large swampy area covered the land to the hills in the south and up into the lower reaches of Creighton Valley. From Lumby to Shuswap Falls the trail passed along the north side of Rawlings Lake. Cox states that the standing and fallen timber east of Lumby made traveling difficult and in places the trail was “completely obliterated”.

Shuswap Falls is not shown on the map, nor is it mentioned on Cox’s covering letter, but one must assume that the river was forded below the falls; this assumption was based on the fact that the Okanagan’s fished for salmon annually below the falls where they forded the river. They used this fishing site up into the 1940’s. Notes on the map state that the expedition had difficulty fording the river at this point.

After crossing the river, Cox with his Indian guides followed the trail upstream to a point opposite Cherry Creek’s entry into the Shuswap from the south. Once more the expedition forded the Shuswap River and this time no difficulties were encountered.

After crossing the river the expedition proceeded up the north side of Cherry Creek. Near the junction of Monashee Creek with Cherry Creek, Cox’s guides recommended that they leave their horses in an open area and proceed on foot. Beyond the open area, fallen timber, tangled brush and dense forest made the use of horses impractical.

From Cox’s map it is impossible to tell for sure which creek, Cherry Creek or Monashee Creek, the expedition followed. A careful study of the map in conjunction with modern maps indicates that they followed Monashee Creek as far as Railroad Creek. Here the expedition stopped because they had run out of supplies and the guides would not proceed any further. Cox drew a sketch, in the lower left hand corner of the map, showing the mountain that was facing them. It looks like The Pinnacles, a group of peaks that tower over 8,000 feet, and although it was the middle of summer, Cox wrote the word “snow” at the top of his mountain sketch. His guides informed him that by following the creek, Barnes Creek, that it flowed into Middle Lake, Columbia River at Needles. While Cox wrote this information on his map, his sketch of The Pinnacles shows that he thought a trail could be built up and over these mountains. In his notes he admits that the trail would be very steep and difficult for horses to climb. Before turning around and returning to Coldstream, Cox put his hand into the bank at Monashee Creek or Cherry Creek and noted that “…fine scale gold was visible amongst the sand that I took out.” In his report he states that he took four handfuls of sand from the creek and washed it in his frying pan. He enclosed the gold dust from his washing with his map and covering letter to the Colonial Secretary.

Cox’s guides informed him that there was a lake further up the Shuswap River, so he drew Sugar Lake on his map with a note beside it saying that he had not seen the lake. On the northwest shore of Sugar Lake are the words “Gold found here by W. Peon.” William Peon was the guide for Father Pandosy and his group of settlers when they walked into the Okanagan from Colvile (now known as Colville) Washington in the Fall of 1859.

The question is, who should receive the credit for the discovery of gold in the area, Peon or Cox?

On his return trip to Rock Creek, Cox fell in with some miners and he told them of his discovery. These miners immediately left for Cherry Creek. There is little doubt that Cox’s discovery lead to the mini gold rush on Cherry Creek.

On the right hand side of Cox’s map is a small, very interesting drawing headed “Indian Map”. This map shows Mabel Lake, Sugar Lake and both Arrow Lakes together with the connecting rivers. Several trails to the Arrow Lakes are marked including one going up Shouswap (sic) River to Sugar Lake. Then up Sitkum Creek, through the pass to South Fostall Creek and down from Fostall to the western shore of the Upper Arrow Lake.

On the trail, just north of Cherry Creek, the Indian guides drew two men wearing top hats and a horse. Cox wrote a note beside the figures stating that three years earlier F. Dischigut (sic) left his horse here and walked over to the Arrow Lakes on the Indian trail. The top hats are significant because only Chief Fur Traders and Indian Chiefs wore them as symbols of their status.

A Summary of Questions and Opportunties

Robert L. de Pfyffer’s analysis about the discovery of gold at Cherry Creek is probably the most important to date. It tells us this may have been the first gold rush in North America started by a government public servant and may have been the closest thing possible to a “planned” gold rush.

However, de Pfyffer also reveals that while W.G. Cox is credited with starting the gold rush, it was William Peon who was the first to discover gold in the Monashee. This leaves us with another question. Could it have been William Peon and François Duchoquette referenced within the Indian Map drawn for Cox? Both men had been Fur Traders with the Hudson’s Bay Company; which might have caused the Indian guides to symbolize them with “top hats”.

But there’s a twist, according to family genealogy records from the Christien family, a pioneering family in Lumby; Louis Christien had arrived with his brother Joseph to the Okanagan Valley in 1858 and the Christien family states that Louis discovered gold at Cherry Creek in 1862.

They say he was with William Peon.

We still need to learn more about these first prospectors and whether or not they were linked together in some way.

Further to Robert L. de Pfyffer’s analysis of the Cox journey in 1862, was the fact that there was no mention of Shuswap Falls. Yet he believed that the expedition forded the river below the falls. It seems strange that Shuswap Falls being such an important physical feature did not appear on the Cox map, nor in his report. De Pfyffer was speculating and admittedly based his analysis on some assumptions.

Researchers at the Almanac did a bit more digging, and came up with another analysis but based on some different assumptions. An unconfirmed report has revealed that the Okanagan People had a settlement in the Bluesprings Valley that may have been larger than the Head of the Lake settlement. While this settlement had probably been abandoned at the time of the Cox trip, any mention of it, would have been of great interest to him because he was identifying possible Indian reserve lands during that same period.

This assumption is coupled with one where Cox’s Indian guides may not have wanted a Colonial agent to see where the location was for one of their best salmon harvesting sites. This assumption suggests that the guides kept Cox away from Shuswap Falls intentionally, and instead, guided him through the Bluesprings Valley which at the time had a pocket wetland that could have been large enough to be defined as a lake. Passing by this Bluesprings lake would have caused the expedition to travel down to the river where Schaffer Road is today, where they might have forded the Shuswap River about a mile upstream from the falls. Given mid summer and low water Cox may have been unaware of a waterfall. Cox noted that to cross the river was a challenge. Crossing a mile upstream from the falls might have been challenging, while a crossing downstream from the falls might have been less of a challenge.

There is much more we need to know about the years before and after 1862. By 1863, where the Gold Panner Campground sits today there was a small community consisting of two houses and one cabin on a claim belonging to two partners, Pion and Louis. Was this William Peon and Louis Christien?

Robert L. de Pfyffer’s story will help define a framework from which a greater understanding can be constructed as we further our search into the history of the Monashee.

(30)

The “Indian Map” portion of the larger linen map that went missing and then was found in 1986.